Transformative Learning in a Polarized Age

August 21, 2023

It will not come as a surprise to you to suggest that we live in an age of great polarization. We consistently read of cultural and political wars that used to exist on the periphery of our experience but now are consistently at the center of our lives. You may have had friends canceled on social media platforms for statements they have made or pictures they have posted. Our politicians, right and left, depict each other in the most extreme forms often labeling the other as “evil” and beyond redemption. At times it feels like we are on the brink of a civil war that may even risk our democracy. What should we do? How should a Christian university live and work in this time?

Our educational communities find ourselves in the middle of this cultural conflict. The ends of the political spectrum compete to control the educational narratives because they know if they control (change) the narrative, then they can narrow future choices. We have seen this recently in our own community as Portland protesters tore down and destroyed the statues of individuals like U.S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln because of the perceived inconsistencies in their words and actions. Especially for Grant and Lincoln, they did not meet the criteria established by political progressives for recognition and honor. Lincoln and Grant simply represent disingenuous white power brokers who sought their own interest at the expense of others. In this type of environment, dialogue has no room for complexity and nuance – all narrative stories must serve the designs of the “future” rather than attempting to make objective truth claims about people and the past.

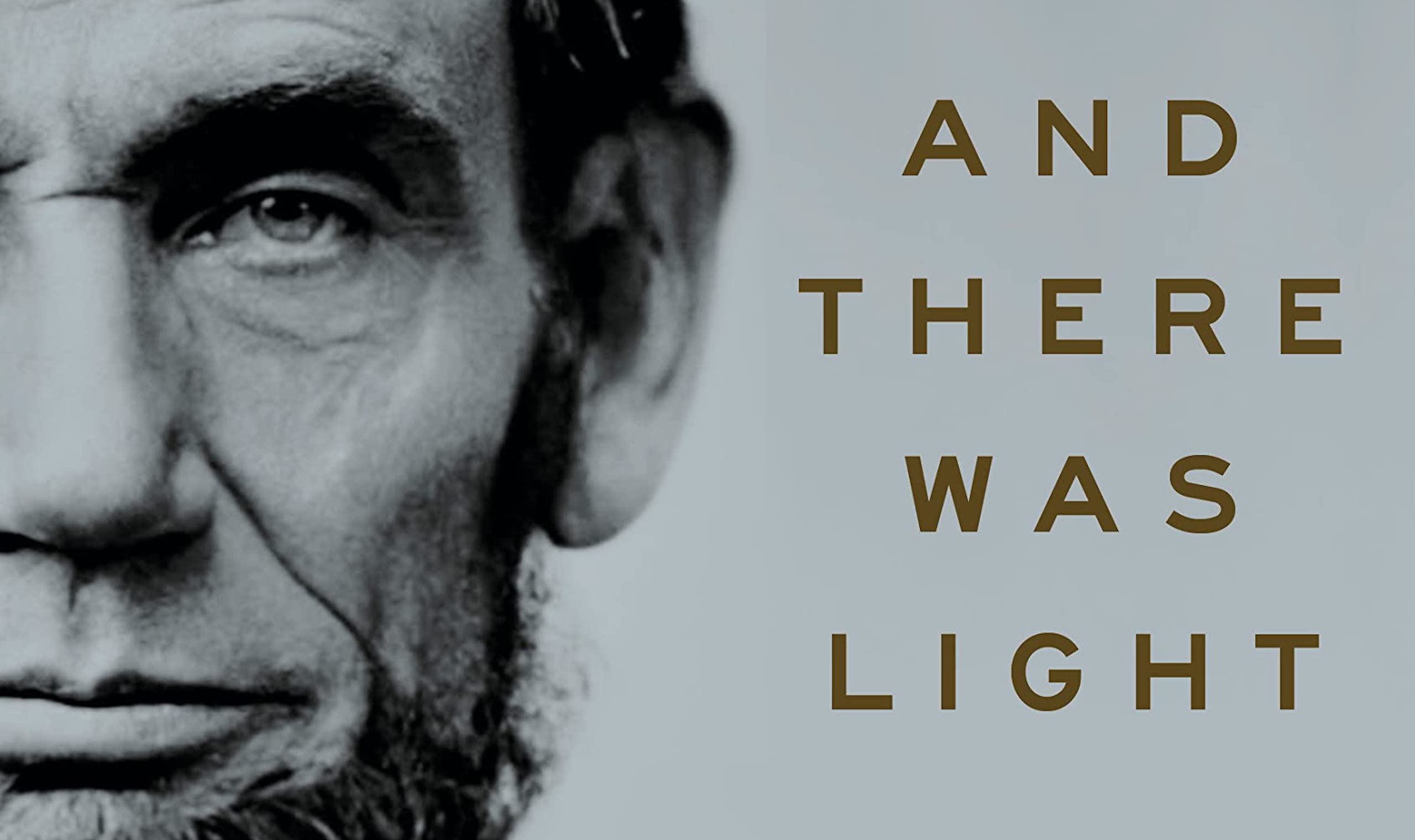

I just completed a new work on Lincoln by Pulitzer Prize winning historian, Jon Meacham, entitled, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle (Random House, October 2022). Disturbed by the recent trends in education (especially history) Meacham sets out to provide a more complete picture of the Civil War and in particular Lincoln’s position on slavery. In this effort, his goal was to completely understand Lincoln’s position on slavery but also to place him in the context of his time. He writes:

I just completed a new work on Lincoln by Pulitzer Prize winning historian, Jon Meacham, entitled, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle (Random House, October 2022). Disturbed by the recent trends in education (especially history) Meacham sets out to provide a more complete picture of the Civil War and in particular Lincoln’s position on slavery. In this effort, his goal was to completely understand Lincoln’s position on slavery but also to place him in the context of his time. He writes:

“For many Americans, to see Lincoln whole is to glimpse ourselves in part – our hours of triumph and of grace, and our centuries of failures and of derelictions. This is why his story is neither too old nor too familiar. For so long as we are buffeted by the demands of democracy, for so long as we struggle to become what we say we already are – the last, best hope, in Lincoln’s phrase – we will fall short of the ideal more often than we meet the mark. It is a fact of American history that we are not always good, but that goodness is possible. Not universal, not ubiquitous, not inevitable – but possible.

Yet to depict Lincoln as only a reluctant warrior against slavery and for an egalitarian future fails to do him justice. To him, slavery was akin to cancer – a deadly disease that one might try to manage but that usually proved fatal “surely there is no way to cure it, to engraft it and spread it over your whole body. That is no proper way of treating what you regard as wrong.

Taken all in all – which is how we should take him, all in all – he was a human being who sought to do right more often than he did wrong.” (Meacham, And There was Light, prologue xxxi-xxxiii)

Meacham makes no excuses for slavery or the racism present in American culture. Words are not adequate to describe the evils of the slave system practiced in the United States nor its long “tail” which emerged after the Civil War in segregation, the Ku Klux Klan, and political and legal systems that systematically and severely limited the freedom of African Americans in the United States. Our struggles with race are certainly the result of choices our ancestors made in our past.

Yet, as Meacham notes, individuals with the character of Abraham Lincoln are indeed the kind of people we need today. In the midst of a society that argued for the positive good of slavery and thought a “Black person” was never the equal of a white person, Lincoln advocated and worked for the equality of all people. Disregarded and hated by people across the political spectrum, a “minority president,” Lincoln held to his moral convictions and found a way to declare slavery wrong and, in the end, held the Union together. Not a perfect man by any means but he showed “that goodness was possible” even in the middle of great division and strife.

George Fox University (originally Pacific College), at the core of its mission, has always had the conviction that a Christian educational institution seeks foremost to develop citizens committed to the pursuit of truth, focused on character, and full of wisdom. Reflecting that commitment in 1951, George Fox College adopted a new motto – “Moulding Futures is a Sacred Trust.” Charlotte Macy noted, “Surely the desire to create, to make, to fashion is an innate divine urge provided in us by the Creator himself, that we should be like Him, and that His cause and Kingdom should progress in the world through the dreams and visions of His people. . . . We are not cogs in a machine moving in one direction regardless of our personal volition or desire. We are craftsmen 'workmen of God,' co-laborers with Christ with the freedom and capacity to dream, to create, to work and see that dream become a tangible reality. . . Our dream is not one of ceramic art, but one of body, soul and spirit so fashioned and marked by the Divine Seal of God’s own hand that its distinction, beauty and practicality in the world shall be noted and respected.” Indeed, our vision is to develop students with character, eventual citizens, who will be the people of God to the World.

Similarly, in 1959, after the college was notified that it had achieved accreditation for the first time in its history, President Milo Ross celebrated. He also pointed to the mission:

“Our college under God, has many reasons for existence. Not the least of these is our adherence to the Christian philosophy of being, that a person is not truly educated until he or she knows God, that all of life can be enhanced and lived better if and when only, as it is lived by the laws in this groove without departing all these years. A host of alumni around the world who are living this kind of life is abundant proof of the validity of our position.

The founders of George Fox were moved by the light shining in the face of Jesus Christ. This college continues in this heritage as it seeks to understand, to refine, to transmit and to embrace the light in trust as seen in the ages and in our own experience. We are living in a tremendous age. The challenge is so great that we might almost faint at the thought of it. It will be your duty and privilege to strive to impart and to fulfill a particular segment of all that which is to be learned. Your first concern is to be concerned with the whole man and woman. This cannot be done by dealing only with the body and the mind. It must by necessity include the soul.

We aim rather to help you (students) find a key to the world’s great libraries with the Bible in the middle of all the books. We aim to help you acquire a new appreciation of beauty, a rich character, a stronger faith, a deeper knowledge, a broader vision of time and eternity, a higher culture and above all else, to know Jesus Christ as the Son of God, and your own Savior, and that your lives may conform to his image.” (Milo Ross, “President Addresses Student Body,” The Crescent, December 4th, 1959)

The accumulation of knowledge and a successful career are not sufficient for a graduate of George Fox University. We aim higher because we want our students to reflect the desires of our God. Our greatest hope is that through mentoring relationships with professors and staff, formal work in the classroom, and engagement on the fields of play our students, allowing Christ to work in their hearts, become something new. They become people willing to risk, to love, to serve their neighbor for the cause of Christ.

As you may know, Oregon has been a challenging place for African Americans in particular. In the early 1930s a young African American, Alan Rutherford, came to Oregon and George Fox to earn his teaching degree. He was heavily involved in the campus serving in numerous leadership roles in student government and the YMCA and he was a member of the track and field team. He also led frequent conversations regarding the challenges of race in America. In 1931, The Crescent noted that he was a man of wisdom and character and the editors recognized that he was facing challenges that no white student would see. The leaders of George Fox worked hard and were able to overcome the overt racial limits and found him student teaching placements. Mr. Rutherford went on to become one of the leading educators in the state of North Carolina and had a school named after him when he retired. (“Black Alumnus Jumps Race Hurdle,” The Crescent, May 5th, 1956)

In the midst of the racism that dominated America and Oregon for much of our history it is true that George Fox could have done better for Mr. Rutherford. Nevertheless, at the height of a segregated culture that severely limited African-Americans, the leaders of George Fox stood for the equality of Mr. Rutherford and they made good possible in a broader community of exclusion. Our commitment to diversity has been long standing even though our progress has been small. It is rooted in our understanding of the Kingdom of God and the type of people and community we wish to be.

It seems to me that Mr. Rutherford’s case is an important one. A university, informed by the teachings of Christ, should always examine its cultural context for change. George Fox President Levi Pennington did so in 1917 when he wrote the Oregon senator at the time to suggest that a citizen could still love his country but refuse to kill another person for whom Christ had died. At the time, there was no such thing as a “conscientious objector” and it was through the arguments of Pennington and other Quakers that the status of “conscientious objector” was created and George Fox graduates in World War II, Korea and Vietnam served their country in the field through human service (Pennington Letters, George Fox Archives, 1917). Our own Fred Gregory served Vietnamese communities at the edge of the war front, constantly risking his own death, for the service of others in the name of Christ.

Transformed people, on the right and the left, make “good possible” in their communities. The work of the university continues in this vein today. This past spring after spring break I was having a book discussion with one of my presidential groups and we were making “small talk” during a break. I asked the group to talk about what they did during spring break. One of the students, Bryce Goetz, a communication major and member of the football team, said, “I went to Ukraine to serve in a refugee community.” He simply stated it as a fact but the jaws of everyone else in the room dropped.

At the same time that many people are going to the beach, home for a week, this young man chose to find a way to get to Ukraine (no easy task in and of itself) and then served for a week before he returned to class. It is a more complex story but Bryce’s choice (with the help of his George Fox mentors) placed him in a tradition of George Fox graduates that are charting a different path formed by their Christian commitment and educational experience at the university.

This type of work does not just extend to the undergraduate program. This past summer, the Physical Therapy program took a team to Uganda working with teachers and local caregivers who serve kids with long-term physical and mental disabilities. They served more than 1,000 patients in numerous clinics providing essential support to the work of local professionals. While the medical service was certainly exemplary, the work of Dr. Ryan Jacobson and his team was genuine “soul” work as well. Micah and Grace Rwothumio who founded University Community Fellowship are pastors and they worship and minister to the whole person. Prior to the work effort in rural Goli, Micah led the group in prayer and preparation before driving nine hours north to the region. Each day begins in prayer with doctors and nurses as we seek to advance God’s healing and work in community. President Ross was right when he noted that the work of the university is only fully advanced when it includes the soul.

This type of work does not just extend to the undergraduate program. This past summer, the Physical Therapy program took a team to Uganda working with teachers and local caregivers who serve kids with long-term physical and mental disabilities. They served more than 1,000 patients in numerous clinics providing essential support to the work of local professionals. While the medical service was certainly exemplary, the work of Dr. Ryan Jacobson and his team was genuine “soul” work as well. Micah and Grace Rwothumio who founded University Community Fellowship are pastors and they worship and minister to the whole person. Prior to the work effort in rural Goli, Micah led the group in prayer and preparation before driving nine hours north to the region. Each day begins in prayer with doctors and nurses as we seek to advance God’s healing and work in community. President Ross was right when he noted that the work of the university is only fully advanced when it includes the soul.

But what of the broader world we live in? Faith and church are on the decline and secularism is on the rise. Will a Christian education even be possible in 10 years? Jake Meador, in a recent article in The Atlantic Daily notes that the data regarding the decline of faith in America is not what it seem. He notes:

“Contemporary America simply isn’t set up to promote mutuality, care, or common life. Rather, it is designed to maximize individual accomplishment as defined by professional and financial success.

Such a system leaves precious little time or energy for forms of community that don’t contribute to one’s own professional life or, as one ages, the professional prospects of one’s children. Workism reigns in America, and because of it, community in America, religious community included, is a math problem that doesn’t add up.” (Isabel Fattal reviewing Jake Meador’s, “Why So Many Americans Have Stopped Going to Church," The Atlantic Daily, Aug 3, 2023)

It is not so much the Church that has forced people out, although that has certainly happened, but the triumph of individualism that has limited the appeal of the Church. Meador asks the question:

“What can churches do in such a context? In theory, the Christian Church could be an antidote to all that. What is more needed in our time than a community marked by sincere love, sharing what they have from each according to their ability and to each according to their need, eating together regularly, generously serving neighbors, and living lives of quiet virtue and prayer? A healthy church can be a safety net in the harsh American economy by offering its members material assistance in times of need: meals after a baby is born, money for rent after a layoff. Perhaps more important, it reminds people that their identity is not in their job or how much money they make; they are children of God, loved and protected and infinitely valuable.

The tragedy of American churches is that they have been so caught up in this same world that we now find they have nothing to offer these suffering people that can’t be more easily found somewhere else. American churches have too often been content to function as a kind of vaguely spiritual NGO, an organization of detached individuals who meet together for religious services that inspire them, provide practical life advice, or offer positive emotional experiences. Too often it has not been a community that through its preaching and living bears witness to another way to live.” (The Atlantic Daily, August 2023)

The good news is that Meador (and the data) suggest that churches that have high barriers, that practice what they preach, that center their lives in the Word, that seek community beyond Sunday morning; that challenge people to engage the world outside the church – these types of churches are not in decline; they are flourishing. The key is that the Church, and people of Faith, must be authentic followers of Jesus – seeking his designs not that of the current culture. Meador quotes Stanley Hauerwas:

"‘Pastoral care has become obsessed with the personal wounds of people in advanced industrial societies who have discovered that their lives lack meaning.’ The difficulty is that many of the wounds and aches provoked by our current order aren’t of a sort that can be managed or life-hacked away. They are resolved only by changing one’s life, by becoming a radically different sort of person belonging to a radically different sort of community.”

That is what George Fox has sought to be from its inception – authentically following Christ the best we can. Tish Harrison Warren is one of my favorite authors and she recently wrote her last editorial for the New York Times. She wrote in leaving, “We can seek to have all the right political opinions and still not really love our neighbors, those right around us, in our homes, in our workplaces or on our blocks. . . . The way to battle abstraction in our time is to embrace the material, the incarnation of our lives, the fleshy, complicated, touchable realities right around us in our neighborhoods, churches, friends and families.”

C.S. Lewis reminded us in his great sermon, “The Weight of Glory” that “there are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilisations — these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.”

To work in a place with the “Be Known” promise ultimately means that we take seriously your place with Christ in the Kingdom of God. Our work is the education and transformation of students – developing them into the kind of people who bring God’s peace and justice to His world. In that effort, we succeed more often than we do fail and we are at our best when we are incarnational – it is when the “Be Known” promise becomes real.

Richard Foster, former pastor of Newberg Friends and faculty member at George Fox University, noted in the 50th anniversary edition of his great work, Celebration of Discipline, “Superficiality is the curse of our age. The doctrine of instant gratification is primarily a spiritual problem. The desperate need today is not for a greater number of intelligent people, or gifted people, but for deep people. The Classical Disciplines of the spiritual life call us to move beyond surface living into the depths. They invite us to be the answer to a hollow world.” (Richard Foster, Celebration of Discipline, introduction to the anniversary edition).

Foster would agree with Warren that, in this era the incarnational part or our lives deserves extra attention. We pray that God helps us focus our attention on the mission – aiming at being a radically different sort of community.