Peace Requires "Active Love"

September 16, 2023

This month I spoke at the unveiling of Newberg’s new dynamic wind-powered sculpture that stands outside the Chehalem Cultural Center. The dedication of the sculpture emphasized peace in our community and called us to experience the world outside ourselves. Peace is a difficult topic for the human community. Our common history is one of violence and the primacy of one cultural view over another. We have fought, killed and destroyed for millennia to advance our position and cause against another. And, in spite of progressive protests to the contrary, the last two centuries have been the worst – we have developed the means to destroy humans in great numbers. It would seem odd, given human history, to believe that peace is possible.

Perhaps we can blame the classics for our plight. The great Roman poet, Horace called Romans to prepare for war in defense of their country. He declared in a poem from the Odes -

To suffer hardness with good cheer,

In sternest school of warfare bred,

Our youth should learn; let steed and spear

Make him one day the Parthian's dread;

Cold skies, keen perils, brace his life.

Methinks I see from rampired town

Some battling tyrant's matron wife,

Some maiden, look in terror down,—

“Ah, my dear lord, untrain'd in war!

O tempt not the infuriate mood

Of that fell lion I see! from far

He plunges through a tide of blood!”

Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori!

Death's darts e'en flying feet o'ertake,

Nor spare a recreant chivalry,

A back that cowers, or loins that quake.

Horace, in his efforts to restore Rome’s hope and martial prowess, believed that the ideal Roman male citizen was one who strove to sacrifice, even to submit to heroic death, on behalf of one’s culture. Indeed, one of their enemies, the Parthians, should fear and quake when they see the Romans coming.

More than 2,000 years after Horace’s call to chivalry and arms the English poet, Wilfred Owen had a much different take on war and human purpose. Written in 1918 amidst the experiences of trench warfare in the Great War Owen penned this –

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime. . .

. . . My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Most often when we talk of peace, we are as Horace and Owen noted, discussing the role of humans in war. I serve an institution that has always sought to refine and balance one’s duty to preserve a “country.” In 1917, President Levi Pennington wrote a letter to Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States, requesting that he consider that Quakers, loyal to their country, might not want to be compelled to serve in World War I through the draft. It is my sincere hope, he wrote, “that you will use your influence to save us from the necessity of facing a choice between obedience to the commands of their country and loyalty to our conception of God’s will for us. We are a loyal people, true to the nation under which we enjoy such signal blessings, and to the flag we love. And we desire to serve our country in any way that will not violate our consciences, nor compel us to violate our religious convictions, so deep that now as many times in the past our people in large numbers would have to choose fidelity to principle, though it might cost us our lives.”

Most often when we talk of peace, we are as Horace and Owen noted, discussing the role of humans in war. I serve an institution that has always sought to refine and balance one’s duty to preserve a “country.” In 1917, President Levi Pennington wrote a letter to Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States, requesting that he consider that Quakers, loyal to their country, might not want to be compelled to serve in World War I through the draft. It is my sincere hope, he wrote, “that you will use your influence to save us from the necessity of facing a choice between obedience to the commands of their country and loyalty to our conception of God’s will for us. We are a loyal people, true to the nation under which we enjoy such signal blessings, and to the flag we love. And we desire to serve our country in any way that will not violate our consciences, nor compel us to violate our religious convictions, so deep that now as many times in the past our people in large numbers would have to choose fidelity to principle, though it might cost us our lives.”

Pennington noted that it was not from physical danger and death that he opposed war as thousands of Friends had died because of their convictions. But the “belief that God does not permit us to kill nor to prepare for killing is so strong with many of us that we must petition you to use your great power to provide for us some other way of serving the country we love.” It took more than a generation but the United States government finally recognized that Quakers could serve their country, even in times of war, in ways that did not force them to participate in killing the enemy. Many did so at the consistent risk of their own lives. Fred Gregory, one of many, served in the mountains of Vietnam during the Vietnam conflict in the midst of the war providing needed service to communities that simply needed help. He and others served for peace in the midst of a painful war.

If we mean by “peace” then the absence of war and conflict, we can be rightly proud that a university in our community has stood for both love of country and against violence and killing in war. At George Fox University we often emphasize that we are indeed a “peace” community. But we should be careful lest we become too proud of our peace commitment. Unfortunately, for those of us who claim to follow the claims of Christ, we are called to a much higher standard than simply avoidance or opposition to war.

As Christ taught, peace was not simply the absence of violence but a characteristic condition of the human heart. Perhaps illustrating Christ’s teaching, Fyodor Dostoyevsky in his book, The Brothers Karamazov, depicts a young woman who visits Father Zosima, a Russian monk who was well known for his wisdom. In response to her distress at no longer being able to believe in the immortality of her soul, Father Zosima invites her to practice “active love.” “The more you succeed in loving,” he notes, “the more you’ll be convinced of the existence of God and the immortality of the soul.” In response to this exhortation, the woman wonders aloud, “Yes, but could I survive such a life for long?” If you are called to serve a sick person who does not respond with gratitude for your service are you still obligated to both serve and love?

What will you do in the face of ingratitude – will you go on loving, or not? We live in a society, (perhaps it is true of all societies), that advocates and practices what we might call the “exchange love.” I will do this for you if I receive gratitude, I gain an honor, I am repaying a debt – quid pro quo. Jesus calls for a much different standard of what we might call “active love.” In the great Sermon on the Mount recorded in Matthew chapter 5, he says – “You have heard the law that says the punishment must match the injury: ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say, do not resist an evil person! If someone slaps you on the right cheek, offer the other cheek also. If you are sued in court and your shirt is taken from you, give your coat, too. If a soldier demands that you carry his gear for a mile, carry it two miles. Give to those who ask, and don’t turn away from those who want to borrow. “You have heard the law that says, ‘Love your neighbor’ and hate your enemy. But I say, love your enemies! Pray for those who persecute you! In that way, you will be acting as true children of your Father in heaven. For he gives his sunlight to both the evil and the good, and he sends rain on the just and the unjust alike.”

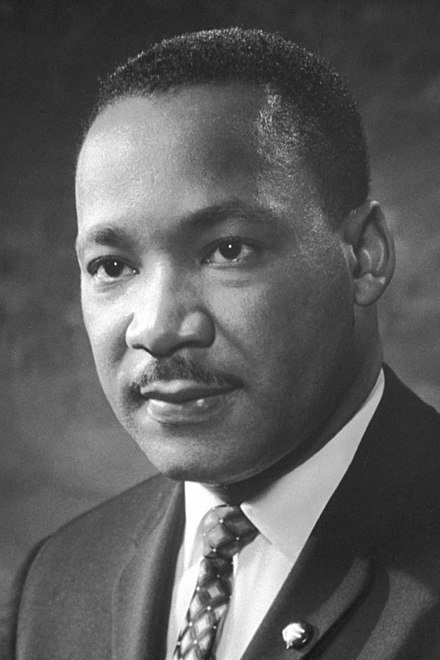

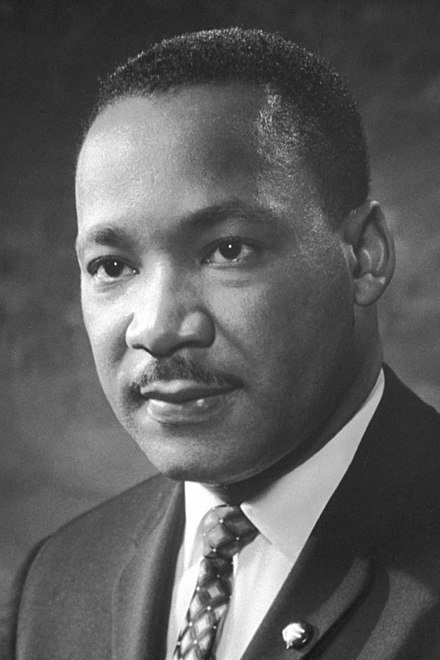

What does it mean to be in a community where “peace” reigns? Where it is more than an ethic, a bumper sticker, or even a sculpture? It is a community that reflects “active love.” Most of us have great respect for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and have great admiration for the Civil Rights Movement. Yet, in our “admiration” we often fail to note that he required specific commitments of those who would serve the movement. Dr. King’s followers had to agree to 10 principles of what I would call “active love”:

What does it mean to be in a community where “peace” reigns? Where it is more than an ethic, a bumper sticker, or even a sculpture? It is a community that reflects “active love.” Most of us have great respect for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and have great admiration for the Civil Rights Movement. Yet, in our “admiration” we often fail to note that he required specific commitments of those who would serve the movement. Dr. King’s followers had to agree to 10 principles of what I would call “active love”:

1. As you prepare to march meditate on the life and teachings of Jesus.

2. Remember the nonviolent movement seeks justice and reconciliation - not victory.

3. Walk and talk in the manner of love; for God is love.

4. Pray daily to be used by God that all men and women might be free.

5. Sacrifice personal wishes that all might be free.

6. Observe with friend and foes the ordinary rules of courtesy.

7. Perform regular service for others and the world.

8. Refrain from violence of fist, tongue and heart.

9. Strive to be in good spiritual and bodily health.

10. Follow the directions of the movement leaders and of the captains on demonstrations.

As Dr. King constantly noted, “non-violent resistance is not a method for cowards. It does resist. The nonviolent resister is just as strongly opposed to the evil against which he protests, as is the person who uses violence. His method is passive or nonaggressive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent, but his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade the opponent that he is mistaken.”

Dr. King dynamically believed in the revolutionary aspect of Christ’s teaching on “active love” and emphasized Christ’s primary concern for who “you” are becoming not what is happening to your enemy, the other. He knew that peace cannot reign at all until hearts are different because the anger and violence that characterizes war is deeply rooted in our own hearts. It is only when our hearts change, when we see the “other” as a neighbor, someone who God created that peace is possible. When we actively serve those we do not share worldviews we have taken the first step towards understanding but most importantly for reframing and healing our own hearts.

In our own community we have struggled between factions of the “right” and the “left.” Each with a different view for flourishing in our community. The broader world calls it a “cultural war.” Wars, even those without guns, leave people divided, angry and with a desire to pay the other side back. “An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.” Those actions cannot be characterized by people who love peace and who seek to serve their neighbors.

I want Newberg to be a place that models peace. During the Black Plague in Europe, as thousands suffered and died, many of the wealthy fled to the countryside to avoid the disease. There were others, primarily motivated by Christian love and compassion, who stayed, at the risk of their own death, to soothe the wounds and suffering of the afflicted. Those individuals expressed a commitment to love their “neighbors” that few might accept today (or even then). Yet their service was ultimately not about their acts of compassion, as great as they might have been, but an actual reflection of who they had become.

If any community is truly to be one that reflects peace, then we must be people of “active love” who seek most to love our neighbors - to desire the flourishing of even those who may be on opposing sides of issues. We choose this action not because we agree – we do not at times – but because we live here, work here, and serve here. We become a community of peace not when we see all issues alike but when, in disagreement, we recognize that we are indeed neighbors and our hearts and minds extend grace to all. We have no “enemies,” only friends who have been created by God. Peace requires “active love.” May it ever be so in Newberg.

Perhaps we can blame the classics for our plight. The great Roman poet, Horace called Romans to prepare for war in defense of their country. He declared in a poem from the Odes -

To suffer hardness with good cheer,

In sternest school of warfare bred,

Our youth should learn; let steed and spear

Make him one day the Parthian's dread;

Cold skies, keen perils, brace his life.

Methinks I see from rampired town

Some battling tyrant's matron wife,

Some maiden, look in terror down,—

“Ah, my dear lord, untrain'd in war!

O tempt not the infuriate mood

Of that fell lion I see! from far

He plunges through a tide of blood!”

Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori!

Death's darts e'en flying feet o'ertake,

Nor spare a recreant chivalry,

A back that cowers, or loins that quake.

Horace, in his efforts to restore Rome’s hope and martial prowess, believed that the ideal Roman male citizen was one who strove to sacrifice, even to submit to heroic death, on behalf of one’s culture. Indeed, one of their enemies, the Parthians, should fear and quake when they see the Romans coming.

More than 2,000 years after Horace’s call to chivalry and arms the English poet, Wilfred Owen had a much different take on war and human purpose. Written in 1918 amidst the experiences of trench warfare in the Great War Owen penned this –

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime. . .

. . . My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Most often when we talk of peace, we are as Horace and Owen noted, discussing the role of humans in war. I serve an institution that has always sought to refine and balance one’s duty to preserve a “country.” In 1917, President Levi Pennington wrote a letter to Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States, requesting that he consider that Quakers, loyal to their country, might not want to be compelled to serve in World War I through the draft. It is my sincere hope, he wrote, “that you will use your influence to save us from the necessity of facing a choice between obedience to the commands of their country and loyalty to our conception of God’s will for us. We are a loyal people, true to the nation under which we enjoy such signal blessings, and to the flag we love. And we desire to serve our country in any way that will not violate our consciences, nor compel us to violate our religious convictions, so deep that now as many times in the past our people in large numbers would have to choose fidelity to principle, though it might cost us our lives.”

Most often when we talk of peace, we are as Horace and Owen noted, discussing the role of humans in war. I serve an institution that has always sought to refine and balance one’s duty to preserve a “country.” In 1917, President Levi Pennington wrote a letter to Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States, requesting that he consider that Quakers, loyal to their country, might not want to be compelled to serve in World War I through the draft. It is my sincere hope, he wrote, “that you will use your influence to save us from the necessity of facing a choice between obedience to the commands of their country and loyalty to our conception of God’s will for us. We are a loyal people, true to the nation under which we enjoy such signal blessings, and to the flag we love. And we desire to serve our country in any way that will not violate our consciences, nor compel us to violate our religious convictions, so deep that now as many times in the past our people in large numbers would have to choose fidelity to principle, though it might cost us our lives.” Pennington noted that it was not from physical danger and death that he opposed war as thousands of Friends had died because of their convictions. But the “belief that God does not permit us to kill nor to prepare for killing is so strong with many of us that we must petition you to use your great power to provide for us some other way of serving the country we love.” It took more than a generation but the United States government finally recognized that Quakers could serve their country, even in times of war, in ways that did not force them to participate in killing the enemy. Many did so at the consistent risk of their own lives. Fred Gregory, one of many, served in the mountains of Vietnam during the Vietnam conflict in the midst of the war providing needed service to communities that simply needed help. He and others served for peace in the midst of a painful war.

If we mean by “peace” then the absence of war and conflict, we can be rightly proud that a university in our community has stood for both love of country and against violence and killing in war. At George Fox University we often emphasize that we are indeed a “peace” community. But we should be careful lest we become too proud of our peace commitment. Unfortunately, for those of us who claim to follow the claims of Christ, we are called to a much higher standard than simply avoidance or opposition to war.

As Christ taught, peace was not simply the absence of violence but a characteristic condition of the human heart. Perhaps illustrating Christ’s teaching, Fyodor Dostoyevsky in his book, The Brothers Karamazov, depicts a young woman who visits Father Zosima, a Russian monk who was well known for his wisdom. In response to her distress at no longer being able to believe in the immortality of her soul, Father Zosima invites her to practice “active love.” “The more you succeed in loving,” he notes, “the more you’ll be convinced of the existence of God and the immortality of the soul.” In response to this exhortation, the woman wonders aloud, “Yes, but could I survive such a life for long?” If you are called to serve a sick person who does not respond with gratitude for your service are you still obligated to both serve and love?

What will you do in the face of ingratitude – will you go on loving, or not? We live in a society, (perhaps it is true of all societies), that advocates and practices what we might call the “exchange love.” I will do this for you if I receive gratitude, I gain an honor, I am repaying a debt – quid pro quo. Jesus calls for a much different standard of what we might call “active love.” In the great Sermon on the Mount recorded in Matthew chapter 5, he says – “You have heard the law that says the punishment must match the injury: ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say, do not resist an evil person! If someone slaps you on the right cheek, offer the other cheek also. If you are sued in court and your shirt is taken from you, give your coat, too. If a soldier demands that you carry his gear for a mile, carry it two miles. Give to those who ask, and don’t turn away from those who want to borrow. “You have heard the law that says, ‘Love your neighbor’ and hate your enemy. But I say, love your enemies! Pray for those who persecute you! In that way, you will be acting as true children of your Father in heaven. For he gives his sunlight to both the evil and the good, and he sends rain on the just and the unjust alike.”

What does it mean to be in a community where “peace” reigns? Where it is more than an ethic, a bumper sticker, or even a sculpture? It is a community that reflects “active love.” Most of us have great respect for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and have great admiration for the Civil Rights Movement. Yet, in our “admiration” we often fail to note that he required specific commitments of those who would serve the movement. Dr. King’s followers had to agree to 10 principles of what I would call “active love”:

What does it mean to be in a community where “peace” reigns? Where it is more than an ethic, a bumper sticker, or even a sculpture? It is a community that reflects “active love.” Most of us have great respect for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and have great admiration for the Civil Rights Movement. Yet, in our “admiration” we often fail to note that he required specific commitments of those who would serve the movement. Dr. King’s followers had to agree to 10 principles of what I would call “active love”: 1. As you prepare to march meditate on the life and teachings of Jesus.

2. Remember the nonviolent movement seeks justice and reconciliation - not victory.

3. Walk and talk in the manner of love; for God is love.

4. Pray daily to be used by God that all men and women might be free.

5. Sacrifice personal wishes that all might be free.

6. Observe with friend and foes the ordinary rules of courtesy.

7. Perform regular service for others and the world.

8. Refrain from violence of fist, tongue and heart.

9. Strive to be in good spiritual and bodily health.

10. Follow the directions of the movement leaders and of the captains on demonstrations.

As Dr. King constantly noted, “non-violent resistance is not a method for cowards. It does resist. The nonviolent resister is just as strongly opposed to the evil against which he protests, as is the person who uses violence. His method is passive or nonaggressive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent, but his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade the opponent that he is mistaken.”

Dr. King dynamically believed in the revolutionary aspect of Christ’s teaching on “active love” and emphasized Christ’s primary concern for who “you” are becoming not what is happening to your enemy, the other. He knew that peace cannot reign at all until hearts are different because the anger and violence that characterizes war is deeply rooted in our own hearts. It is only when our hearts change, when we see the “other” as a neighbor, someone who God created that peace is possible. When we actively serve those we do not share worldviews we have taken the first step towards understanding but most importantly for reframing and healing our own hearts.

In our own community we have struggled between factions of the “right” and the “left.” Each with a different view for flourishing in our community. The broader world calls it a “cultural war.” Wars, even those without guns, leave people divided, angry and with a desire to pay the other side back. “An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.” Those actions cannot be characterized by people who love peace and who seek to serve their neighbors.

I want Newberg to be a place that models peace. During the Black Plague in Europe, as thousands suffered and died, many of the wealthy fled to the countryside to avoid the disease. There were others, primarily motivated by Christian love and compassion, who stayed, at the risk of their own death, to soothe the wounds and suffering of the afflicted. Those individuals expressed a commitment to love their “neighbors” that few might accept today (or even then). Yet their service was ultimately not about their acts of compassion, as great as they might have been, but an actual reflection of who they had become.

If any community is truly to be one that reflects peace, then we must be people of “active love” who seek most to love our neighbors - to desire the flourishing of even those who may be on opposing sides of issues. We choose this action not because we agree – we do not at times – but because we live here, work here, and serve here. We become a community of peace not when we see all issues alike but when, in disagreement, we recognize that we are indeed neighbors and our hearts and minds extend grace to all. We have no “enemies,” only friends who have been created by God. Peace requires “active love.” May it ever be so in Newberg.

Loading...

Loading...